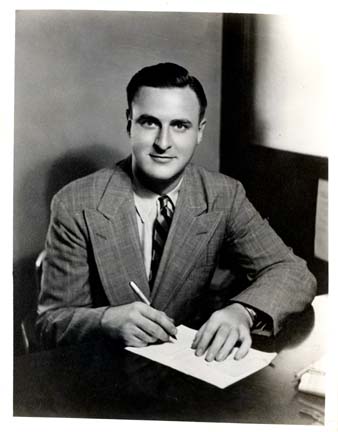

Bucklin Renssalear Moon (1911-1984):

Alumni, Literary Editor, and Renowned Author

|

Born on May 13, 1911 to a lumberman, Chester

D. Moon, and his wife, Edith Bucklin Moon, Bucklin Rensslear originated in

Eau Claire, Wisconsin. He had two sisters, Marjorie and Peggy, and

eventually moved to Winter Park, Florida with his family. Moon received his

early education from various preparatory schools, such as Snyder School in

Captiva Island, Rivers School and Fressenden in Massachusetts.

After his expulsion from Fressenden for a “childish transgression,”[1]

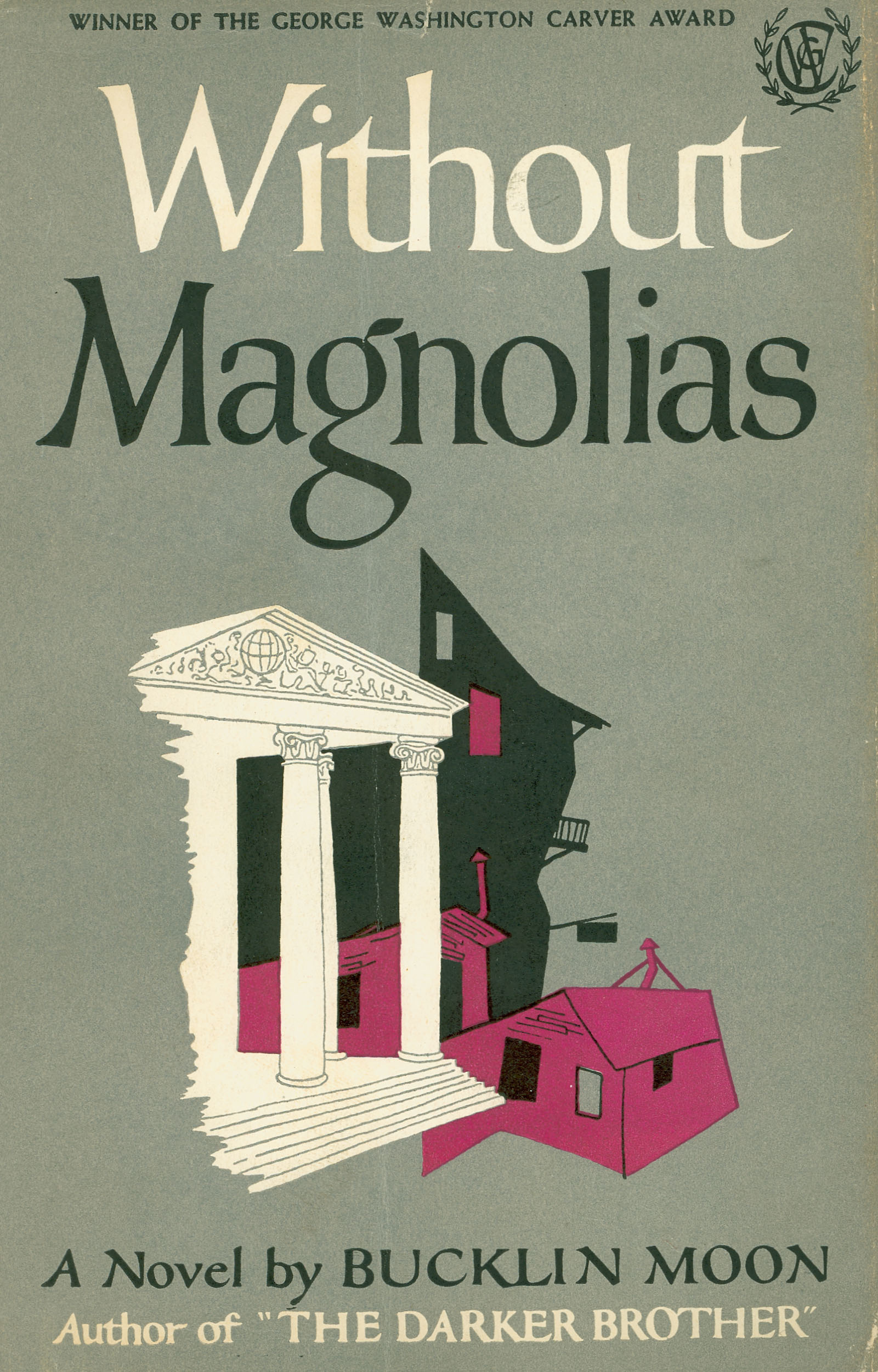

he attended Shattuck Military Academy in

Fairbault, Minnesota. O Moon experienced a vibrant, liberal Rollins atmosphere.[2] During the time he attended the College, beginning in 1929, Hamilton Holt had begun enforcing a radical educational model, emphasizing student-centered conference plans rather than the traditional lecture format. Moon joined the local X-Club fraternity, the football team, and became the associate editor for the school publication, Flamingo. Socially, he became friends with Zora Neale Hurston and in 1936 married a fellow Rollins student, Elizabeth (Betty) Frederica Vogler, with whom he had a daughter named Deborah. He eventually had three other children: Bucklin Jr., Abigail Jordan, and Sarah Lucey. Moon graduated with an Artium Baccalaureates degree in history in 1934; he took five years to graduate because he withdrew as a sophomore for two terms in order to work on a stuttering problem. After college, Moon worked from home for several years, where he wrote stories and reviews. Afterwards, he moved to New York to become a reader, and then an editor for Doubleday from 1941 until 1951. Moon also wrote or edited books considered significant to the black community, such as The Darker Brother (1943); A Primer for White Folks (1945), which made Moon the first white to publish an anthology of writings by and for an American black audience; The High Cost of Prejudice (1947), an economic analysis; and Without Magnolias (1949), which won the George Washington Carver Award for best book of the year written by, or concerning, blacks. He left Doubleday after ten years to serve as a fiction editor for Collier’s Magazine, but in 1951 the U.S. House Un-American Activities Committee accused Moon of joining the Communist Peace Offensive.[3] Moon denied any such affiliation. In addition, publications such as Commonweal criticized the accusations. Despite the various protestations regarding the charges, however, Collier’s fired Moon in 1953. The accusation proved to be an event that largely ended his writing career and, emotionally, affected him greatly.[4] Moon edited the Doubleday Anthology in 1962 and eventually returned to editing under Pocket Books’ new imprint, Trident Press. After his divorce he married Ann Curtis Brown and moved to Marco Island, Florida. Following her death he wed Cornell science graduate, Marion Heldt. He settled in Tavernier and died in Plantation Key on September 19, 1984 from an illness. He left behind a memorable legacy despite the personal tragedy caused by the charges of communism, owing to the achievement of creating unique, largely non-stereotypical literary portrayals of black families in America.[5] - Angelica Garcia For more information, see the Bucklin Moon Manuscript Collection in the Rollins College Archives. [1] Maurice O’Sullivan, “Total Eclipse,” (Rhea Marsh & Dorothy Lockhart Smith Winter Park History Research Grant Report 2002), 2. [2] Ibid., 6. [3] House of Representatives Committee on Un-American Activities, “Report on the Communist ‘Peace’ Offensive: A Campaign to Disarm and Defeat the United States,” April 1, 1959, Washington D.C., 108. [4] O’Sullivan, “Total Eclipse,” 10. [5] Ibid., 11. |

||||

| Project Home | List of Names | Rollins Archives | Olin Library | Rollins College |