American Playwright and Author

|

Article as originally featured in Rollins Alumni Record, Vol. 67:2 (Summer 1989), 14-17.

When

author and award-winning playwright Jess Gregg was 21 and a senior

at Rollins College, his first short story, The Grand Finale, was

published in Esquire. Certainly the plot had the boldness of youth:

an apparently multi-gratified composer had five mistresses. The

trouble began when he realized he was dying and concluded that his

mistresses were coming around so often he couldn't get his work

done. In the imaginative denouement, the young Gregg had the

composer pretend to die five times, in turn, in the arms of each of

his mistresses. While these examples may adequately reflect the boldness and industry of the undergraduate imagination, they do not adequately anticipate a successfully sustained literary career that was to span at least five decades, a career that has not been without inner and outer conflict between two all-compelling callings: one to the novel, the other to the theatre.

His skills and

accomplishments as a playwright have sometimes associated Gregg with

such luminaries of the theater as Joshua Logan, Elia Kazan, Hal

Prince, and the longtime Gregg family friend, the late Gower

Champion, as well as with well-known actors and actresses.

Playwriting, especially during the revisions-during-production

phase, often involves travel and can be a social and learning

experience for the playwright, if he so chooses. The writing of

novels, however, is essentially a loner's calling. Virtually no

group decisions are involved in the writing of first drafts of

novels. Although he writes and speaks quite often of this at times

frustrating and perhaps-at-times sublime rivalry, there is little

doubt, when decision time is at hand, as to which of these muses he

more readily responds. Any writer, year in and year out, must

constantly decide what to undertake next-an often difficult

determination. "What I work on next," producer Stephen Spielberg

once said, "is the most important decision I ever make." The facts

are that Jess Gregg's long string of high-quality work includes

twice as many plays as novels, even though he is presently finishing

the first draft of a 400-page novel that, so far, has taken nearly

four years to write. Which again brings back that rival muse, playwriting. A part of those nearly fifty months of fleshing out the novel was spent revising two plays. One, The Underground Kite, which opened in Central Florida in February of this year, underwent revisions -- some after Gregg talked with actors about their conception of their parts. Another play, the musical comedy Cowboy, written with composer Richard Riddle, toured 11 western states in '87 and '88. "I no longer know," he said recently, "whether theatre is a blessing or a curse in my life. But saying no to it never crosses my mind."

The late Dr. Edwin

Granberry, Professor Emeritus of Creative Writing at Rollins, was

both an author and a playwright. During the years, he and his former

student read and criticized each other's drafts and scripts. Gregg

calls Granberry's influence "simply enormous." He even dedicated his

issue of the R Book to his mentor: "From most, advice is small

change. From him, it is a legacy." "I was," Gregg wrote on a 1988 Christmas card, "full of gratitude that I knew him and learned from him and kept up with him all these years. I came from California to Rollins because of him. When I was a teenager in Beverly Hills High School and my father realized I was serious about writing, he made a thorough investigation of writer's workshops and teachers. All roads led to Granberry." Gregg's next stop after Rollins was a year at Yale Drama School. "Then," he says, "I sat down at the typewriter." He wrote first, not a play, but two novels. The first, The Other Elizabeth, was published in 1952. It attracted immediate attention, appearing initially in the Ladies Home Journal, but, he says, "so cut down as to be creepy, if not embarrassing." The book sold well, was widely published in Europe, remained in print for years-in one language or another-and is still going the rounds on TV. Novelist Kay Boyle wrote that she had discovered the book while in prison for civil disobedience. Actress Bette Davis phoned one day to tell the author how much she liked it. "It was made for me!" she said.

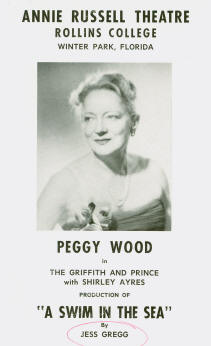

One reason Gregg

and his father had decided on Rollins as the best place to begin was

Granberry's reputation as a perceptive, as well as lyrical, regional

novelist. "In a sense," Gregg says, "The Other Elizabeth was

a regional novel, although today it might be called a Gothic. My

second book, The Glory Circuit, which dealt with itinerant

evangelists in Florida, was my first truly When this writer first came under the spell of its deft dialogue and consistent "real people," The Glory Circuit seemed to possess much more valid regional perceptions on this subject than I had found elsewhere, even in Sinclair Lewis's powerful Elmer Gantry. Unfortunately, this novel came out during a newspaper strike. "It sold poorly," says the author, "but Marilyn Monroe did want to play the white trash waif, Millie Marie. That put some rainbow into the experience." Jess Gregg's first play, A Swim in The Sea, was brought out by Hal Prince, producer of Cabaret, West Side Story, and Phantom of the Opera. It was, as they say, a great way to start. It played Philadelphia and other cities-even, eventually, the Annie Russell Theatre at Rollins. But, like hundreds of other American plays, it never came to New York. His second play, however, made England-in a conspicuous way. That was The Sea Shell, produced in 1960 by Stephen Mitchell and starring Sean Connery and that grand old actress and friend of George Bernard Shaw, Dame Sybil Thorndyke. But how to sustain the art and skills needed for the long pull he had aligned himself for? For an actor, that sometimes means understudying an accomplished star. For Gregg, it meant assisting accomplished directors and producers. As early as the mid-fifties, his apprenticeship with three of the New York theatre's best-known directors and producers began. Joshua Logan, who masterminded such hits as South Pacific and Mr. Roberts, hired him as his assistant on Fanny. He also worked as an assistant to Elia Kazan on Tennessee Williams' Cat On A Hot Tin Roof. Choreographer and director Gower Champion used him in four shows, including Hello Dolly and I Do, I Do. Champion was, he says, his most important lifetime influence. They had grown up together in Los Angeles, their two families had been close for over a century-and Jess watched Gower grow into a major figure in the Broadway theatre. "He came to hire me because he was surrounded by people who only agreed with him, and he needed someone he could trust to argue with him when his ideas weren't first-rate. Sometimes it got pretty sticky. We'd start talking about the show about a month before rehearsal, but my real work was during the out-of-town try-out where the show usually takes shape. Sometimes I didn't know if I would emerge with a job, much less a friend."

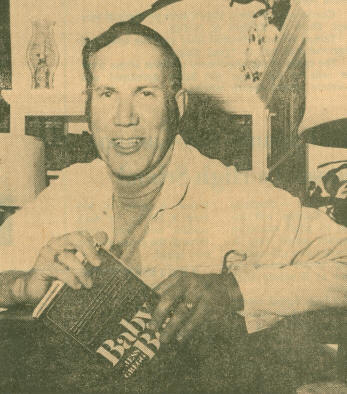

The friendship

apparently survived, however, for Gower named his first son after

Gregg. Champion's early death was a great blow to Jess. In 1964, Gregg's play, Show From The Rooftops, was produced off-Broadway. Later, three one-act plays with an all-male cast, The Men's Room, also appeared off-Broadway; of these, The Organ Recital at the New Grand won the John Gassner Award. In the '70s, Gregg did the Broadway adaptation of an old Jerome Kern musical, Very Good Eddie, which played 90 performances at the Booth Theater. Meanwhile, he did not forget the regional novel, or the investigative research required to dig it out and properly phrase it. A Florida ramshackle fish camp run by a man who hired ex-convicts provided the spark. "From talking to ex-cons," he says, "I became interested in the problems of the convict's upside-down existence in prison: living among enemies, the food, the humor, all of it. And the eventual problem of going out into the free world again. Finally I wrote the Florida Department of Corrections asking to be allowed into the penitentiaries for study. I told them I was not interested in sensational matter; my research would be simply to report. Somehow, they dared to let me, and I was given carte blanche to come and go in the Florida penal colonies. I even served at one of the road camps as a guard-without-gun." The experience mined enough human lode and authentic patterns of regional speech to fill, so far, a novel, a play, and a one-actor. Baby Boy, the novel, came first-in 1973. Its look behind the locks had an unsentimental sensitivity about it reminiscent of John Steinbeck's Of Mice and Men. Baby Boy was selected as Book-of-the-Month Club alternate. It was optioned by Hollywood, and Gregg went west to his old childhood home to write the screenplay for director Robert Mulligan (To Kill A Mockingbird). Several other screenwriters were assigned to it. The story, as usual, got further and further away from the book. Eventually, it was optioned by Twentieth Century Fox, and later by Oliver Stone. "Now," he says, "somebody else has it, and I'm afraid Baby Boy will be an old man by the time it's done." Image courtesy of Orlando Sentinel Star, (January 3, 1974).

In Florida prisons,

an "underground kite" is a message slipped out of jail. Several

years ago, Gregg's most recently produced play, The Underground

Kite, won a contest sponsored by Florida's Theatre-in-the-Works,

and in 1987, was presented for five performances as a "staged

reading"-first step towards production. Both Jess's sister, Jenelle,

and her husband, Howard Bailey, participated. Jenelle read the part

of Lorraine, a tourist, and Howard, who had directed Jess in plays

at Rollins long before, read "Gator," the Florida cracker who ran

the fish camp on the Huwatchee River.

"But this time," he

adds, "I was allowed to work very closely with the director, Ed

Dilks, and even encouraged to discuss the play with the actors. As a

result, it was the kind of collaborative effort the theatre is

supposed to be. The cuts suggested themselves painlessly, and a week

after the curtain came down, I had the revisions ready for the

script's next step-whatever that may be." As the playwright knows best, chance plays the role of a giant in the American theatre. Jess never promotes or sends anything out on his own. According to Jenelle, he doesn't even read, much less save, reviews. The way he divides things, the game of "Huwatchee The Kite?" is best played by his New York agent. His musical play, Cowboy, roughly based on the life of Charles M. Russell, the cowboy artist, was first tried out at Connecticut's prestigious Goodspeed Opera House in the mid-'70s. It has since had a number of productions regionally. Two years ago, it opened at the University of Montana's sparkling new theatre, and a year later, the State of Montana, in celebrating its Centennial, presented the show in a tour of the far and middle western states. It was also given a three-week New York showcase; but when the concrete canyons of that city will be ready for a full production of the play is anyone's guess. This is a question for the rest of us, not a seasoned veteran like Jess Gregg. "Regional writing," he says matter of factly, "hasn't attracted much support from the commercial theatre, but it has gradually found audiences away from New York." At this writing, Jess Gregg is busy at his typewriter with what Jenelle admires as "his tunnel vision about writing. I've seen him take an entire day, or longer, in trying to get a sentence exactly right. Between his two work places, New York and Winter Park, he's totally absorbed in his work." His current absorption is a novel, four years and four hundred pages along. In the waggish spirit of his undergraduate days, he gives the same working title to any play or novel in progress: No Bed Of Her Own. The real titles come later. He's been around long enough to have earned some traditions. Another is that he exerts no effort studying or following trends. And he doesn't talk about-or "talk away," as Hemingway once put it-any work in progress.

However, New York novelist Don

Matheson, author of Stray Cat and the forthcoming Ninth Life,

provides one insight: "I think of him as a writer who has a rare

degree of commitment to quality. He avoids cheap tricks. He writes

very slowly. He spends all day, every day, around his work. He is

very good at turning a phrase. More importantly, he has the strength

to put his phrases in the right setting.

For the rest of us,

the new novel is something to look forward to: as a book, yes; as a

play, maybe; as a movie, who knows? Jess Gregg has trained himself

to do it-almost in his head-all three ways. - Bill Shelton '48 |

||||

| Project Home | List of Names | Rollins Archives | Olin Library | Rollins College |