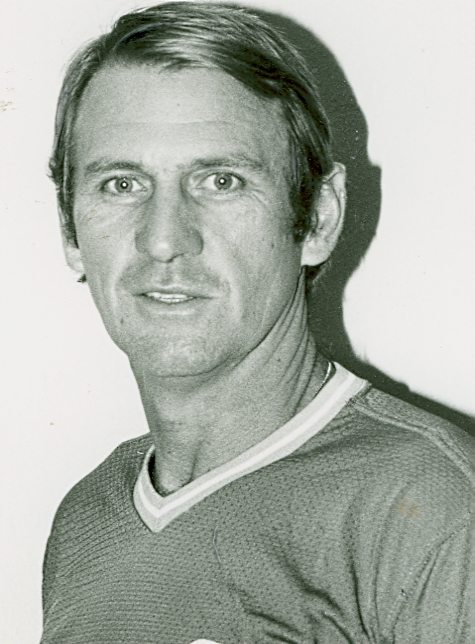

Boyd Coffie (1937-2006):

A Life Well LivedBoyd Coffie's drive sliced sharply and landed in the woods – on top of a tree root. Down by five strokes in match play with only a par-four hole remaining faced the mathematical certainty of losing this round against partners. Now I've got them where I want them he told himself. Ill give them one more chance."

“OK, mano a mano, all bets are off winner

takes all on the last hole," he announced.

Lord, a confidant of Coffie for 40 years and

one of his early protégés, was telling this story and laughing so hard he

had difficulty getting the words

out. Such is the state of grieving for a man who may have influenced as many

lives as anyone in the history of Rollins College.

When he died May 2 at age 68 from cancer in his hometown of Athens,

Tennessee, Howard Boyd Coffie ’59 ‘64MAT left a legacy in human

terms the lives of those he touched.

"My whole management style and way of living my life are based a principles and values I learned from Boyd," said Lord, whose own father died when he was 16. “His rules were simple: Stay out of trouble, show up on time, play hard. And he expected you to do well in the classroom.

Coffie’s accomplishments as player and coach are well documented but tell only part of his story. Above all, he was a teacher and, some would say, a philosopher. Baseball was his medium, the conduit for leaving his imprint on those who crossed his path.

His life, said Tom Kinsman 76 '78MBA, "wasn't about wins and losses. It was about how he dealt with people." When Klansman became men’s' basketball coach at Rollins, Coffie was there as a mentor. Lesson one: Understand what is important. Don't live and die with every game. Do everything right and the wins will take care of themselves. Stand on principle, even if it means you lose.

"He changed my life immeasurably by his fairness and integrity," said Vic Zollo '73, who transferred to Rollins from the University of Vermont his junior year solely based on Coffie's reputation.

Former Rollins third baseman John Castino '77 knows something about principle and its role in his education.

As the Tars were warming up for the 1976

season and Castino's first year of eligibility for the draft, Castino

urgently needed to leave campus to attend to a personal matter involving

competition for his fiancée’s attention. He told Coach Coffie he would

return in time for the season opener.

"OK, Johnny, but you have to realize there are consequences," Coffie

warned. Castino wasn't worried.” I said, `OK, whatever," Castino recalled.

"He might make me run eight miles; everybody would know it, and that would

be the price to pay.”

Castino returned to find his name missing

from the lineup card. The scouts were there. This was to be the biggest day

of his college career. Castino rode the bench. Rollins lost the game.

"I

confronted

Boyd in the locker room," Castino said. "I was furious. But I learned an

important lesson that day. He taught about following the rules. Not many

people do that today."

"I

confronted

Boyd in the locker room," Castino said. "I was furious. But I learned an

important lesson that day. He taught about following the rules. Not many

people do that today."

Castino, who was co-Rookie of the Year his first of six seasons with the

Minnesota Twins, had a final thought: "I ended up on the President's List

because of Boyd Coffie. I went to the major leagues because of Boyd Coffie."

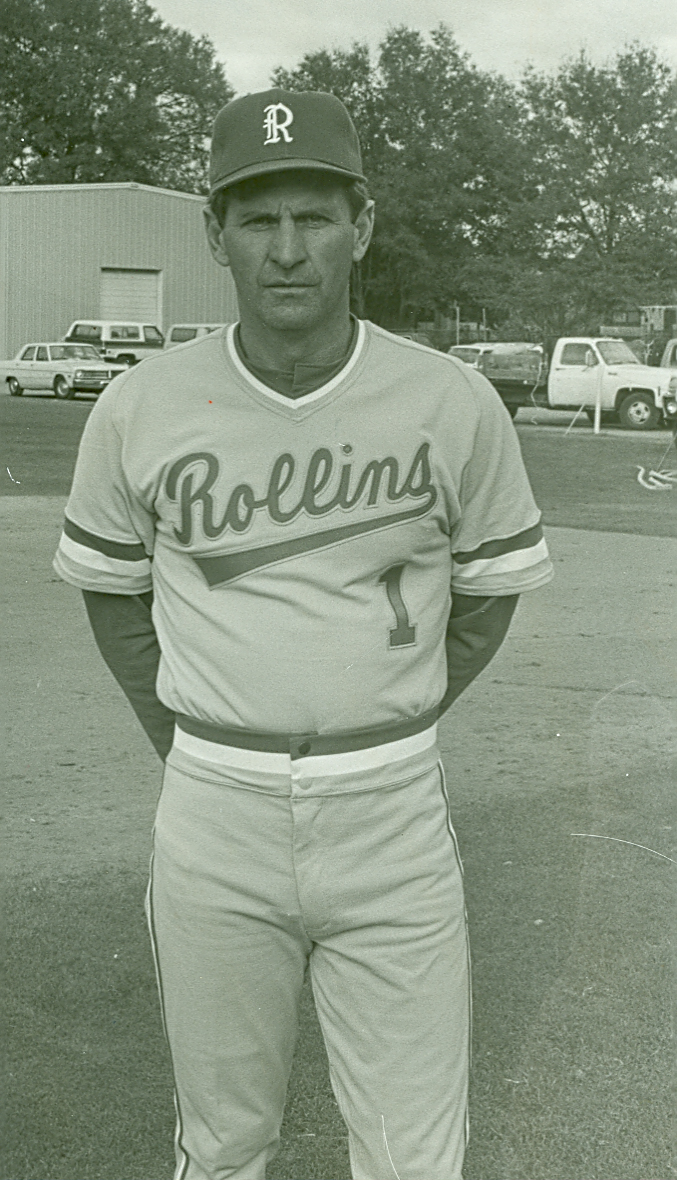

This is the defining characteristic of Boyd Coffie. The legendary Rollins baseball coach could have worked anywhere in professional baseball or at a Division I school. He was comfortable away from the limelight and never lost focus on his mission.

"He treated everyone the same, whether it

was the person who cut the grass or Mr. Shirley, an 80-year-old man he took

under his wing," said Winchester, who was one of Coffie's closest friends.

"It didn't matter whether you were the star or the bottom man on the totem

pole."

Todd Barton '84 is an example

of how the legacy of one person takes on a life of its own. A high-school

English teacher, Coffie's former player teaches as he was taught. "My

students think they are gaining these traits from me," he said. "But in a

very large sense, they are getting them from Boyd Coffie."

In a world where tough talk and brush-back pitches define the communication style, Coffie was something of an oddity. Jack Billingham, who pitched for the Cincinnati Reds in three World Series, found his inspiration watching Coffie play at Rollins when Billingham was a high-school student. "I don't know that Boyd ever said a bad word about anyone," he said, "and I can’t imagine anyone saying anything bad about him."

Boyd Coffie did not come up the easy way. His father left when Coffie was 13, leaving his mother and grandmother to raise him. But Coffie was a gifted athlete who by high school had caught the attention of college recruiters-and 14-year-old Linda Quails.

"My 8th-grade math teacher told me you have to get over to the high school to watch this guy play basketball," Linda Quails Coffie '62 '78MS recalled. They were married in 1962 and had two children who followed in their parents' Rollins footsteps: Ashlie '85 '89 MBA and Trey '90 '92MAT.

After a stellar college baseball career followed by three seasons in the minor leagues, newly married Coffie wanted to settle down. He accepted an offer from his former Rollins coach, Joe Justice '40, to coach basketball and assist in baseball. Coffie had nothing to lose: The Tars had gone 0-26 the year before, and he would have most of the team back.

Lord was Coffie’s student manager, trainer, and sounding board. Lord and Coffie drove the two team station wagons on road trips.

Coffie’s job wasn't easy. "Jimmy Oppenheim

['68] couldn't have been five feet tall," recalled Bob Richardson'68,

Sandspur sports editor at the time and sports statistician. "At Miami

University, Oppenheim guarded a guy who scored something like 59 points that

night against Rollins.

"One time at Eckerd," Richardson said, "we had four guys playing zone and one guy playing man-to-man. Phil Kirk ['67] could shoot from half court but not from anywhere else. This is the kind of thing Boyd had to deal with. He had all these problems, but the thing that is remarkable is that he took all of this in stride." Rollins won four games Coffie's first year. Much later, near the end of his run, the Tars beat Georgia. Some things were going right.

Lord wasn't an athlete. He was, however, dangerously overweight. The constant view of Coffie working out and staying in shape encouraged him to change his lifestyle. He lost 100 pounds, which saved his life when he underwent quadruple bypass surgery, his surgeon told him.

Lew Temple '85 credits Boyd Coffie for saving his life, as well. Temple's career has taken an unusual route, and that is what makes him an interesting character. Too small for the big leagues but in love with baseball, he shagged roles as a bullpen catcher in Seattle and Houston, and then pursued different kinds of roles-on stage and screen. After years of traveling, he found success in the form of steady work in Los Angeles. Four years ago, however, he was near death.

After being fired from a movie contract because of serious illness he would not own up to, he landed at M.D. Anderson Hospital in Houston, diagnosed with a rare form of leukemia and a 40 percent chance of survival. At one point during his 8-month hospital stay, when he was slipping in and out of lucidity while taking continual chemotherapy, he received a phone call from Coffie.

"I would hear from him occasionally when he had heard through the grapevine that I was getting a little too big for my britches," Temple said. "You know, like when we players know just a little too much about baseball. I don't know how he found out about my illness, but he did. He reminded me about who I was and what I had done, this small boy who overcame all those things that stood in my way, and told me that this was just a hill for a high-stepper. He talked to me-not tersely, but not with pity. He reminded me of the fight I was in, and how I could take care of this.

“I got this call from my coach. He told me I was going to be OK, and I was going to be OK.”

At his own funeral, Boyd Coffie once again did what he had done well for so long. His protégés has come from afar and from eras spanning 30 years to say farewell. There were tears from grown men-and a lot of laughter in the celebration of a life well lived. Lord reflected on the event. "In the end," he said, "Boyd brought everybody back into a team.

All the fuss would have embarrassed him. Flashing that impish grin, he would have told each of them, "Son, make the adjustment!" For some, that will be the coach's toughest assignment yet.

A celebration of Boyd Coffie [was] held in the Knowles Memorial Chapel on August 13, 2006 at 2:00 p.m.

-Stephen M Combs ‘66