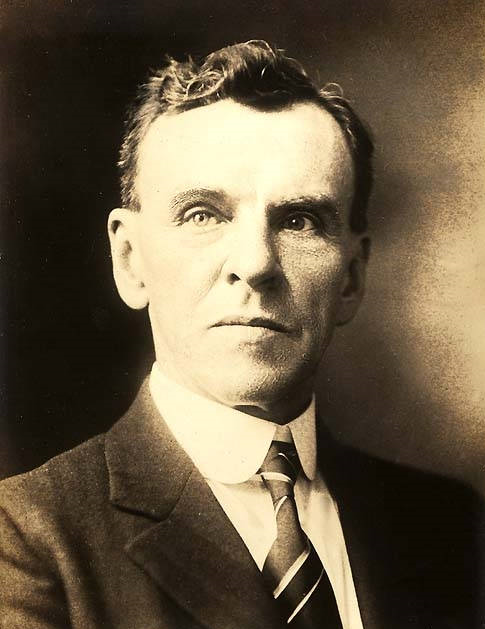

Edwin O. Grover (1870-1965):

Professor of Books and Citizen of the Community

Edwin Osgood Grover was born in Mantorville, Minnesota on June 4, 1870. His father, Wesley Grover, was a congregational missionary to the Northwest Territory at that time. When Edwin was a few years old, his family returned to New England and his childhood was spent on the coast of Maine and in the mountains of New Hampshire. His love of nature was developed while roaming the woods and working in the fields, and this affection remained throughout his life. In 1890 he graduated from St. Johnsbury Academy in Vermont, and then worked his way through Dartmouth College where he graduated in 1894. It was there that he developed his literary interests, reporting for the Boston Globe during summer months and editing the Dartmouth Literary Magazine in the last two years of his college life.

Shortly after graduation, Grover went to Harvard for graduate study. But he soon abandoned that plan and decided to see the world with only $300 in his pocket. For seven months he traveled through the old continents from the Shetland Islands to Algeria. The cost of his round trip by steerage was $19.60, and of his entire voyage $345. Returning to America in 1895, he worked for several years for the Ginn & Co. as a textbook representative in the Midwest. In 1900 he married Mertie Graham, a childhood friend and a graduate of Mount Holyoke College. Shortly after, he was promoted assistant editor of Ginn’s Boston office. In 1901 he become the chief editor of Rand McNally in Chicago, and in 1906 he formed his own publishing company where he was the editor and vice president for several years. In 1912 he sold his interest and became president of the Prang Company, whose crayons and watercolors were well known at the time. In that capacity Grover remained active in promoting the industrial arts movement and art teaching in America. However after “serving a sentence of 30 years in the publishing business,” Grover was ready to retire. Then a call from Hamilton Holt in 1926 changed his life.

The idea of a “Professor of Books” originated from Ralph Waldo Emerson, who wrote in his essay on books in 1856: “Meantime the colleges, while they furnish us with libraries, furnish no Professor of Books, and I think no chair is so much wanted.” Upon becoming the President of Rollins College, Holt saw the cultural possibilities in Emerson’s suggestion, and believed it suited his hope of making Rollins an ideal small liberal college. He made Grover his first faculty appointee as America’s first “Professor of Books.” Some years later Grover recalled “the thrill which I experienced when I came upon Emerson’s suggestion which was to change my life work and make my new vocation also an avocation. My imagination immediately took wings and I began to mull over the possibilities dormant in Emerson’s idea.”[1]

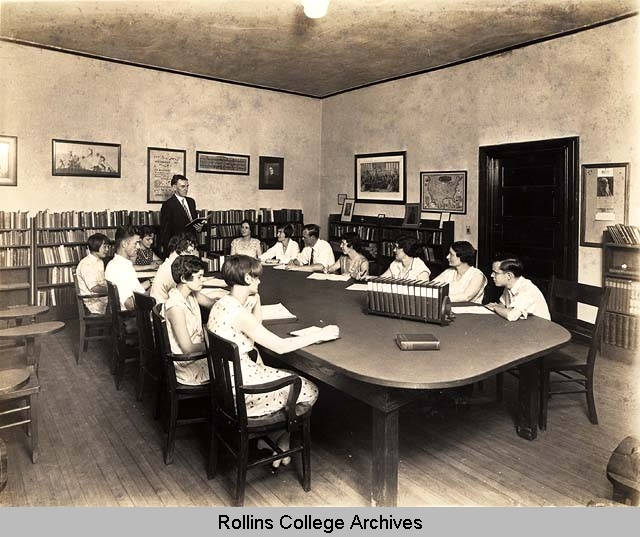

At

Rollins, Grover taught three courses through the Department of Books: the

History of Books, Literary Personalities, and Recreational Reading. To avoid

the formality of the conventional classroom, and secure closer and

friendlier contacts with the students, Grover asked the carpenter to build

him a large oval table, 14 by 6 feet, surrounded by 20 comfortable oak arm

chairs. The walls of the room were hung with a score of pictures – framed

pages of old books, block prints, lithographs, autograph portraits and

letters. More than a thousand books in every literary field filled the

shelves in the room. From this setting Grover made great personalities come

alive, and for more than two decades he helped his students discover romance

between the covers of good books, and establish reading habits that would

last through their lives. The arrangement was so successful, Holt promoted

it as the new Rollins Conference Course. This collaborative study method is

still a cherished learning style at Rollins today.

At

Rollins, Grover taught three courses through the Department of Books: the

History of Books, Literary Personalities, and Recreational Reading. To avoid

the formality of the conventional classroom, and secure closer and

friendlier contacts with the students, Grover asked the carpenter to build

him a large oval table, 14 by 6 feet, surrounded by 20 comfortable oak arm

chairs. The walls of the room were hung with a score of pictures – framed

pages of old books, block prints, lithographs, autograph portraits and

letters. More than a thousand books in every literary field filled the

shelves in the room. From this setting Grover made great personalities come

alive, and for more than two decades he helped his students discover romance

between the covers of good books, and establish reading habits that would

last through their lives. The arrangement was so successful, Holt promoted

it as the new Rollins Conference Course. This collaborative study method is

still a cherished learning style at Rollins today.

Because of his literary interests and business background, Grover helped students publish the college’s first literary magazine Flamingo in 1927. He and William Yust established the Book-A-Year Club in 1933, which during the ensuing years generated steady revenues for the college library. Grover was also the editor of the Rollins’ Animated Magazine for more than two decades, and served as the librarian and vice president of the college. To recognize his achievement, the University of Miami and Rollins College awarded him honorary degrees in 1929 and 1949.

Besides being an accomplished academic, Grover was also very active in community affairs. He was a charter member of the University Club of Winter Park, and helped found the first bookstore in town named the “Bookery.” More notably, Grover played a leading role in the improvement of interracial relations during the early twentieth century. He served as a trustee of Bethune-Cookman College for some years. In 1930, he encouraged his wife Mertie Grover and Mrs. Clarence Vincent, wife of the pastor of the Congregational Church, to start a day nursery for children of black working mothers in Winter Park. When Mertie died in 1936, Grover asked that no flowers be sent to the funeral; instead funds were received toward the establishment of a children’s library on the west side of the town. In 1937, the Hannibal Square Associates was incorporated and Grover served for about ten years as its president. In that capacity he had raised $20,000 for the West Side Community Center, $2,500 for the Hannibal Square Memorial Library, and $13,000 toward the building of the Mary DePugh Nursing Home in Winter Park.

One

of the enduring contributions Grover made to the central Florida community

was the founding and development of the Mead Botanical Garden. Since he

moved to the region in the 1920s, Grover had befriended Theodore L. Mead

because of his interests in nature. When the renowned horticulturist passed

away in 1936, Grover visited Mead’s ranch in Oviedo to see whether it could

be converted into a botanical garden for Rollins College. Then John H.

Connery, who grew up as one of Mead’s Boy Scouts and studied at Rollins in

the 1930s, suggested the swamp by Pennsylvania Avenue in Winter Park. Upon

exploring the site with Connery the next morning, Grover was so excited,

that on the same afternoon he visited the Orlando real estate office of

Walter Rose, a state senator and the owner of the property, and successfully

persuaded him to donate the twenty acres for the proposed project. After

that, he talked Orange County and the City of Winter Park into contributing

additional properties; and moreover, his determination convinced R. F. Leedy,

J. A. Treat and Mary Bartels to give their lands for the cause.[2]

To develop the garden, Grover was also instrumental in securing two grants

from the Works Progress Administration totaling more than $62,000. With

strong local and federal support, the construction of the fifty-five acre

park began on January 9, 1938, and Grover presided over the ground breaking

ceremony. Since the official opening of the Mead Botanical Garden on January

15, 1940, Grover had served as its first president for ten years until he

retired from Rollins College. Despite his retirement, Grover remained a

lifelong supporter of the garden. He was still actively seeking funding for

the park when he was in his nineties.

One

of the enduring contributions Grover made to the central Florida community

was the founding and development of the Mead Botanical Garden. Since he

moved to the region in the 1920s, Grover had befriended Theodore L. Mead

because of his interests in nature. When the renowned horticulturist passed

away in 1936, Grover visited Mead’s ranch in Oviedo to see whether it could

be converted into a botanical garden for Rollins College. Then John H.

Connery, who grew up as one of Mead’s Boy Scouts and studied at Rollins in

the 1930s, suggested the swamp by Pennsylvania Avenue in Winter Park. Upon

exploring the site with Connery the next morning, Grover was so excited,

that on the same afternoon he visited the Orlando real estate office of

Walter Rose, a state senator and the owner of the property, and successfully

persuaded him to donate the twenty acres for the proposed project. After

that, he talked Orange County and the City of Winter Park into contributing

additional properties; and moreover, his determination convinced R. F. Leedy,

J. A. Treat and Mary Bartels to give their lands for the cause.[2]

To develop the garden, Grover was also instrumental in securing two grants

from the Works Progress Administration totaling more than $62,000. With

strong local and federal support, the construction of the fifty-five acre

park began on January 9, 1938, and Grover presided over the ground breaking

ceremony. Since the official opening of the Mead Botanical Garden on January

15, 1940, Grover had served as its first president for ten years until he

retired from Rollins College. Despite his retirement, Grover remained a

lifelong supporter of the garden. He was still actively seeking funding for

the park when he was in his nineties.

Grover passed away in Winter Park on November 8, 1965. His legacy lives on, as his portrait greets visitors to the Rollins College Archives, the West Side Community Center and the DePugh Nursing Home when they open their doors to local residents every morning, and in dazzling flowers in the Mead Garden blossom each spring.

- Wenxian Zhang