Donald Cram (1919-2001):

Alumnus and Nobel Prize WinnerArticle as it originally appeared in The Rollins Alumni Record, Volume 65: 4, Winter 1988.

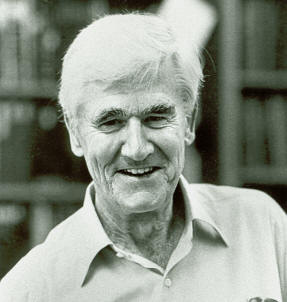

At a press conference during the week he was to receive the Nobel Prize for Chemistry, Donald Cram '41 exhibited his characteristically good sense of humor. Relaxed during his first official meeting with the press and the other honorees for Nobel Prizes in chemistry, physics and economic sciences, Cram attempted to put it all into perspective, and at the same time, put everyone at ease.

"Someone

asked me if I won the Nobel Peace Prize for Chemistry'," Cram quipped to

the gathering at the Royal Academy of Sciences. "I had to tell them `No, I

won a piece of the chemistry prize.' "Clearly at his best when "on stage,"

the affable research scientist seemed at ease, confident and in control.

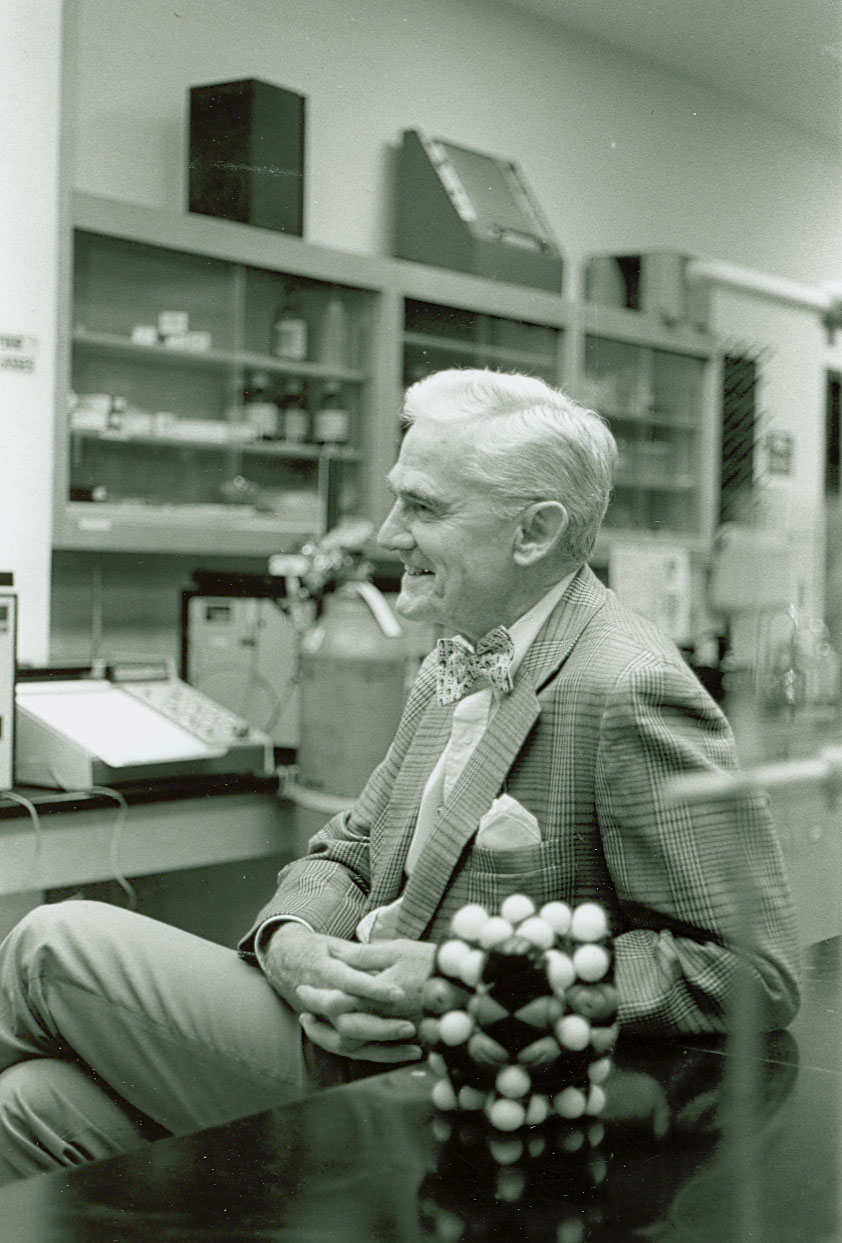

Wearing one of his 150 "trademark" bow ties and flashing a boyish grin, the

68-year-old UCLA professor produced a plastic model of one of his

synthetically-produced chemical compounds. Using the model to demonstrate,

Cram explained how the principle of host-guest chemistry works. In the

process, he demonstrated a type of charm

that has made him a popular

professor and mentor to thousands

of chemistry students in the U.S. and around

the world. Cram, who majored in chemistry during

his undergraduate years at Rollins,

shares the Nobel Prize with Dr.Jean-Marie Lehn of Strasbourg,

France and Charles J. Pedersen of

Salem, NJ. The three were cited for

their work in synthesizing

molecules that mimic important biological processes. The announcement from The Royal Academy of Sciences said that Cram, Lehn and Pedersen have laid the foundations

of what is today one of the most

active and expanding fields of chemical research, a field for which Cram has

coined the term "host-guest" chemistry while Lehn calls it "supramolecular"

chemistry. The research could have widespread implications for environmental

and medical science, and for energy production.

of chemistry students in the U.S. and around

the world. Cram, who majored in chemistry during

his undergraduate years at Rollins,

shares the Nobel Prize with Dr.Jean-Marie Lehn of Strasbourg,

France and Charles J. Pedersen of

Salem, NJ. The three were cited for

their work in synthesizing

molecules that mimic important biological processes. The announcement from The Royal Academy of Sciences said that Cram, Lehn and Pedersen have laid the foundations

of what is today one of the most

active and expanding fields of chemical research, a field for which Cram has

coined the term "host-guest" chemistry while Lehn calls it "supramolecular"

chemistry. The research could have widespread implications for environmental

and medical science, and for energy production.

According to Cram, research scientists are just beginning to develop the field. "We have just scratched the surface," he said.

Cram attended Rollins on a National Honorary Scholarship, worked as an assistant in the chemistry department, and was active in theater, Chapel Choir, Lambda Chi Alpha, Phi Society, and Zeta Alpha Epsilon. But the road to Stockholm had its beginnings long before that.

"I grew up on Aid to Dependent Children," Cram revealed during a candid interview at his hotel. "My parents were immigrants to the U.S. My father was Scottish and my mother was a German, who rebelled against a strict Mennonite faith. From my father's side of the family, I learned English upper class values. From my mother, I learned to love English literature. I think that made me something of a romantic," he confided.

Cram was the only male in a family of five that suffered financial hardships, he said, because of the untimely death of his father. "My father died when I was not quite four," he said, "so I learned how to work at an early age."

Cram tried just about every odd job imaginable, from picking fruit to tossing newspapers, to painting houses. Growing up in the small town of Chester, Vermont, he bartered for things like piano lessons.

"I would offer to cleanup or perform odd jobs in order to learn music," the Nobel laureate revealed. "By the time I was 18, I must have had at least 18 different jobs," he said, "but I learned how to amuse myself by making games out of everything. I would create games to break the monotony, and that is a strategy I continue to use, even in my research."

From his childhood, Cram says he learned the lessons of hard work and self-discipline, but he also learned to be creative, and to be a creative planner of time. "I'm not all that bright," he claimed. "Mainly, I'm creative, and I'm also single-minded. If I become interested in something, I stick to it."

Another value he learned from his family was that "education was the path to righteousness." When he read a notice about an Honors Scholarship to Rollins, he applied. "President Hamilton Holt came to New York and interviewed me," he said. "The scholarship provided a great opportunity. It opened doors, and it allowed me to grow up in a very nice environment. "While studying at Rollins, Cram was able to develop his love affair with chemistry, an affair that began with his first high school course. "There was an instant fit between me and chemistry," he acknowledged. "I thought it was fun and creative. I thought that going into research in chemistry would give me an opportunity to do something new every day."

At Rollins Cram worked

as an assistant

in the chemistry department and became known for building his own chemistry

equipment. He credits professors Guy Waddington and Eugene Farley with being

mentors and

"father figures," and for helping him pursue

career goals that required graduate

training. "They wrote letters of recommendation to about 17 graduate schools," he

recalled. "I was accepted at three, and

finally attended the University of Nebraska.

Ironically, I have since lectured at every

one of those schools, and I delight in reminding them that they turned me

down for graduate study."

At Rollins Cram worked

as an assistant

in the chemistry department and became known for building his own chemistry

equipment. He credits professors Guy Waddington and Eugene Farley with being

mentors and

"father figures," and for helping him pursue

career goals that required graduate

training. "They wrote letters of recommendation to about 17 graduate schools," he

recalled. "I was accepted at three, and

finally attended the University of Nebraska.

Ironically, I have since lectured at every

one of those schools, and I delight in reminding them that they turned me

down for graduate study."

For that matter, Cram has lectured at most major research universities in the world. He won a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1955, was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1961, and has won numerous American Chemical Society Awards for his work in organic chemistry. Rollins honored him with its first Distinguished Alumnus Award in 1915.

He is the author of more than 350 research papers and eight books on organic chemistry. He has taught graduate and post-doctoral students from 21 different countries. Even without the Nobel Prize, his legacy to chemistry is of major significance, says Professor Erich Blossey of the Rollins chemistry faculty.

Cram began his professional career in chemical research at Merck Laboratories during the war years. He worked in penicillin research under the tutelage of a hard-driving and devoted scientist named Max Tischler. From Merck he went to Harvard, where he studied with Paul Bartlett and Robert Burns Woodward. According to Cram, Woodward, who received the Nobel Prize in 1965, was the greatest organic chemist of this century. "He received one Nobel Prize, and I believe he could have received two if he had lived," Cram said during the interview in Stockholm.

Cram began his teaching career at UCLA in 1947, and that, like chemistry, was "an instant fit." "I grew up with a provincial school that went on to become a fine national university," he said.

Although he says that research is a gamble and that only about 20 percent of it pays off, Cram's career was productive, he claims, "because I tried to be creative and flexible and I was willing to move from one field to another. I ended-up in a type of chemistry that has yielded very quickly."

It was around 1975, when a scientist in Zurich, Switzerland won a Nobel Prize for his research on the stereochemistry of organic molecules, that Cram first became aware that he was competitive for the world's most distinguished award. He has since been nominated regularly for the Prize.

Asked about the environment for scientific research in the United States, Cram replied that it is good because "we encourage originality. When you combine that with discipline, it forms the basis for good science and good scientists."

His career has not been

without sacrifice, said Cram, who admitted that his two wives also have

sacrificed for his career. His first wife

was Rollins classmate Jean Turner '41, who

received a master's degree in social work

from Columbia University. His present wife, Jane, is a former chemistry

professor at Mt.

Holyoke. Cram called her

"an inspiring

and unsparing critic."

wife

was Rollins classmate Jean Turner '41, who

received a master's degree in social work

from Columbia University. His present wife, Jane, is a former chemistry

professor at Mt.

Holyoke. Cram called her

"an inspiring

and unsparing critic."

Cram said he chose not to have children "because I would have been either a bad father or a bad scientist."

Although he has received numerous honors throughout the world, Cram treasures the Nobel Prize as a "symbol of excellence." Established in the will of Alfred Nobel, the Swedish chemical engineer who invented dynamite, the Prize is presented to "those who have conferred the greatest benefit on mankind." On December 10, the former Rollins financial aid student received his award from the King of Sweden.

When asked what advice he would have for future generations of Rollins students, Cram replied, "Be single-minded; love what you are doing and make it the centerpiece of your life."

That does not mean you shouldn't have fun, Cram explained. "I have had a lot of fun, and when I am not working I indulge in sports that provide total escape." His great loves are surfing, skiing and mountain climbing-sports that he admits are violent, dangerous, and romantic.

Despite his exalted status as a research scientist, Cram said he still enjoys teaching. In fact, he has even taught introductory courses for non-science majors. The "Cram creativity" came into play when he brought his guitar into class to help break the ice for his students.

"Chemistry is not everything in my life. I have friends outside of chemistry," he said with a grin. "I really do."

-Suzanne McGovern